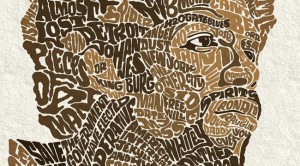

The revolution will not be dramatized: Gil Scott-Heron autobiography focuses on trivial details

It’s suggestive that the quotations on the back cover of The Last Holiday: A Memoir, the new autobiography penned by writer and singer Gil Scott-Heron speak to Scott-Heron’s significance as an artist and not the importance of this book. Common calls Scott-Heron “one of my inspirations” and Eminem says, “Scott-Heron influenced all of hip-hop.” These statements are certainly valid. Too bad the autobiography doesn’t go into the how and why behind such bold claims. Instead of telling us how exactly he came up with a song like “The Revolution Will Not be Televised,” a sardonic tune that brought the ‘60s to end and foretold the way mass consumption would corrupt the activist movements that had brought about such radical change in that tumultuous decade, Scott-Heron fills The Last Holiday with a series of trivial details about his upbringing and then flashes forward to an early ‘80s tour with Stevie Wonder. It’s possible he just doesn’t remember the important stuff. “I always doubt detailed recollections authors write about their childhoods,” he admits in the prologue. But it seems more likely that he’s simply unable to describe his artistic process in the kind of way that would shed a light on its significance.

Scott-Heron’s story begins with his birth in Chicago in 1949. Shortly after his birth, his parents divorce and he moves to live with his grandmother in Jackson, Tennessee. Scott provides plenty of insignificant details about his childhood, revealing that “by the time I was eight or so, I could cross large streets and run errands.” While he does mention that the local black newspaper introduced him to Langston Hughes’ poetry, little in the first seven chapters suggests how his artistic vision might have been molded when he was a child.

After his grandmother’s death, Scott-Heron’s mother returns to Jackson to take care of him and eventually moves to New York when Scott-Heron is in eighth grade. “I didn’t want to go,” Scott-Heron admits. At school, Scott-Heron gets into trouble for sneaking in to play the piano but even here, Scott-Hernon gets tangled up in trivial details about the principal’s attempts to expel him.

In 1967, Scott-Heron winds up at Lincoln University because “it seemed to be a place where Black writers had come to national prominence.” He becomes enraged at a student’s death due to a lack of good health care at the school and stages a protest (he writes about the incident in a particularly pretentious “interlude” in which he seemingly refers to himself in the third person as “the artist”). Other than noting he was surprised some radio stations played tracks from it, Scott-Heron doesn’t say much about his seminal first album, 1970’s Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. In passing, Scott-Heron mentions meeting reggae star Bob Marley and reveals little in describing his relationship with Arista Records head Clive Davis.The last couple of chapters in the book focus on Scott-Heron’s 1980 tour with Stevie Wonder, but Scott-Heron again focuses on things like the nicknames he gave his tour mates and trite conversations he had while driving from gig to gig.

Ultimately, this is a disappointing overview of a significant black poet and writer’s career.