Jimmy Jam: Creating a Body of Work

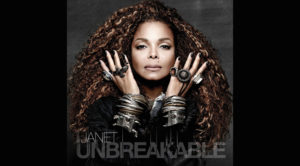

James Samuel “Jimmy Jam” Harris III and Terry Steven Lewis are an American R&B production team that’s left a notable legacy, both with their own group the Time and as the guys who worked behind-the-scenes to turn Janet Jackson albums such as Control and Rhythm Nation 1814 into monster hits. They reunited with Jackson recently for Unbreakable, her ninth studio album. It’s their first collaboration since 2006’s 20 Y.O. Harris spoke via phone from his Los Angeles home.

I know she hasn’t been inducted, but how do you feel about Janet Jackson’s Rock Hall nomination?

I think it’s always nice to be recognized for your accomplishments. The fact that she’s been on the ballot is good and well-deserved. She’s obviously had a long career and one that shows no signs of slowing down. She will continue to be relevant and part of the discussion moving forward. Things happen the way they’re supposed to happen. I’m a big believer in that. I’m happy that she was on the ballot.

Talk about how you and Terry Lewis first met each other.

Well back before electricity—certainly, before fax machines and iPhones and all that kind of good stuff—we were broth junior high school students and met at a summer program at the University of Minnesota called Upward Bound. We were studying to be peer teachers. The concept was that if you learned math you would teach the grade below you math and it would be easier for the kids to understand. I was always a good student, but I was horrible at math and I had no clue why they chose me for the program. I was happy that they did. It gave me a better understanding of math. Even better, I met Terry. I think that was the summer of 1972.

Was music part of the discussion?

Oh yeah. We were staying in dorms, which was awesome. I remember walking into the room and he had this red, black and green bass. He was playing a Kool & the Gang song. I thought that was really cool. I was basically an only child. I have older brothers and sisters but I grew up in the house myself. I think I was 13 and he was 15 and he was that cool kid that everybody wanted to know. We definitely talked music. I was really into pop music big-time. I was waiting for the Chicago VI album to come out. I said something about it to him. He said what about the new Earth Wind & Fire album. He introduced me to them. I remember the first records. It was Earth, Wind & Fire, Tower of Power and a group called New Birth. He totally turned me onto that. That was our conversation. We went back and forth about music.

How long did it take you to put a band together?

Probably a couple of weeks. When the session was ending for the summer, they wanted to have a dance, and they needed a band. Terry knew a couple of guys, including Jellybean Johnson and a couple of other guys. He needed a keyboard player and I told him that I didn’t really play keyboards. There was a lunchroom in the school that was abandoned for the summer. They had stored pianos and I found them. I would play them because my dad could play. He used to hear me play. I said I could play drums but I heard Jellybean play and knew I couldn’t play drums. He was incredible. We put a band together and played the dance. We didn’t have a singer. We played instrumental versions of everything. I know we played the records that I referenced. We played New Birth and Tower of Power’s “Soul Vaccination” and “What is Hip?” and Stevie Wonder’s “Tuesday Heartbreak.” We were playing musically challenging songs but we just didn’t have a singer. But that was the seeds that turned into Flyte Tyme and eventually the Time.

How were you first introduced to Janet Jackson?

She came to a Time concert in Long Beach. She was in the front row with her mom and couple of other people. I remember our show as a little bit risqué and it was kind of funny but she was jamming and loving every minute of it. Afterwards, we got a chance to meet her. She was super sweet. She was a huge Time fan and that was very cool to us. That was the first time we met her and then we met her again in the summer of 1982. She was working on her first album with Leon Sylvers. He had taken us under his wing and given us opportunities to do some records. We did “High Hopes” with S.O.S. Band and we did “Love Finds Its Own Way” with Gladys Knight & the Pips. Our paths crossed a little bit from time to time. She was always really sweet.

Talk about working on 1986’s Control. What was that experience like?

Control was great. Looking back on it, my perspective is different. As it was happening, we had a great time making it. The best part was getting to know her and then personalizing what the album was and having her involved in the writing and lyrics. We did it in Minneapolis, which was great because it was away from the craziness of L.A. and the whole recording scene. Nobody really cared. It was made in a vacuum. When we asked her to come to Minneapolis, there was no hoopla. The record company wasn’t paying attention, other than John McClain, who did A&R. It wasn’t until we were done that John took the album back and started playing tracks that people were like, “Wait a minute. What is this?” It was a great way to make a record and a great way to get to know her. And it was a blueprint we’ve subscribed to with any artist. As producers, our best thing is to make the artist sound good and stay out of the way rather than try to dominate with a certain sound and all that. That’s never been our thing. We want to make the artist sound great and give everyone their own sound. That case best illustrates that. We had a chance to explore that on her album. We did the whole album. That’s the other thing that’s a distinction. We did the whole album rather than two songs here and there.

That album is really funky.

Being around Prince for quite awhile, the funk is definitely there. I think it’s a cool sounding record but that’s partly because we recorded it ourselves, and we really didn’t know what we were doing. We had an engineer walk out on us right before we started recording and we had just built the studio. It was lot of mistakes but under Steve Hodge, who mixed the album, he turned our mistakes into some sonic genius. I give him the credit for that. He was nice enough to stick round and teach us how to record. Sonically, it stands up. A lot of the sounds you hear today are reminiscent of how that record sounds.

When you were working on 1989’s Rhythm Nation 1814 did you have some sense that it would become a major release?

It’s tough to say. I can’t remember what our expectation was. We thought it was a good record. At that point, we felt like we did what we set out to do. On Control, we liked the songs and thought it was good. On Rhythm Nation, we had a higher bar but we were better writers and producers. We were better at our craft. She was a better writer and singer. We knew each other. And we knew what we could do well and couldn’t do well. On that record, we hit the ground running. She walked into the studio and we were doing the track to “Miss You Much.” We were playing it and she got a smile on her face. I played a note on the keyboard and counted her off and that ended up being the string part. That was the spirit of the record. It just happened organically, though we took our time to do it. It was a six-month project. We felt good about it. One thing that gave us confidence as a project was that when we done with everything a certain point, we had to get the budget for the video. She wanted to do this long-form video. It was going to be a million dollars to do what she wanted to do. She wanted to play it at some point. I told her to not play it in the [record label] office. I said she should take the guy on a ride up PCH and play him a couple of things and get his reaction. She called me back later that day and said we got our budget. That meant that the record label was into it. It’s always important that you have to have people behind you who believe in the project. They trusted us, which was great. They were pleased with what they heard, so we were really happy about that.

Talk about working together on Unbreakable. Did you only agree to do it if you could work together like you had in the past?

She led the charge on that. We all wanted that. A lot of time had passed between us working with her. I don’t by any means disown any Janet record that we were involved with, even the ones we weren’t involved with. They all have their place and their influence. I feel like the Janet records that were done in the way we would prefer to do records with her stopped at All for You, which was 2001. We were talking 14 or 15 years. In that sense, hindsight being 20/20, it was easy to have conversations and look back at the past potholes, speed bumps and detours and see that we needed to be on a different smooth road. Once it was agreed upon, it was a no-brainer. She led the charge on that.

The theme reflects various experiences over the course of her life—including aspects of her childhood and the loss of Michael and socially conscious messages.

The process was much the same as the records that I talked about — the first five albums. We would always do the same process. We would compile whatever music we enjoyed, in this case over the last 15 years, though we didn’t go back that far. We listened to a lot of music. We’d sit in a room and listen to things we loved from the past. It’s every eclectic. She loves Brazilian music. It’s a lot of James Brown and Sly & the Family Stone. It’s everything. You name it, and we listened to it. We do that and talk about lyrically what she wants to talk about. She lived a lot of life. She’s in a place where “wise” is the word I would use. There’s a point in your life when you think you know everything and you’ve learned everything you can learn. We all go through that. It’s not true. She’s been through that enough times where her viewpoint on things is that she’s still learning and growing and hasn’t figured it out. There’s no shame in that. I am wise about knowing what I know and don’t know. I think that’s the viewpoint that the album takes. With that as the overall theme, it’s easy to craft songs in that way.

And how does being involved from start to finish affect it?

It makes it a more cohesive body of work. To me, that’s the reason you have albums. People say you can just pick songs. That’s true that people can pick songs. I think people can appreciate an actual body of work. For those people, this is one of the records that like that.

It must be great to read the positive reviews and know you were right to work on it on your own.

Yes, but we had collaborators on the record. The difference is that we picked the collaborators and there wasn’t any outside influence there. As someone who’s worked with Terry for over 40 years, I don’t have a problem as a collaborator because I’ve worked with him for over 40 years. The bigger thing is that the saying “too many cooks in the kitchen” rings true. There was a time when some of her records suffered from that. The other one is that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” This was a case where there were two other collaborators that I should mention. The first one is a guy Thomas Lumpkins. He was great. She brought him along and played some of his tracks two years ago. She said, “What do you think of this?” I said, “I love this. It’s great.” Nothing happened. When we started the record, we were sent a whole bunch of songs as soon as we started. Not everyone knew about it but people who did sent us music. She would listen and go, “This would be good if we do this.” I said, “Why would we take anything we need to change? We can write our own songs.” I played her the two Tommy songs she had sent me two years ago as examples of song that didn’t need to be fixed. I played those songs. It was me and her and our engineer. They both got big smiles on their faces. If somebody doesn’t send us something that makes us feel like this does, then forget it. At that point, we knew he would be one of the people who we would collaborate with. We had been working for a few months and now we’re now at the point where the record company hadn’t heard any songs. We invited those guys to the studio – Venus Brown and Zach Katz. We were going to play a couple of things. We had maybe three things we felt comfortable with just to give them a sense of the direction. I think we played “After You Fall” and “Shoulda Known Better” and I can’t remember what the third one was. They were coming from three different places. When we played the records, the best comment was, “It sounds like Janet.” I said, “Great, that’s what I want to hear.” They wanted us to hear some different writers. At that point, we played a few songs and none of them were necessarily good. The last song I liked but it wasn’t right for Janet. That was a writer called Dem Jointz. They asked us to set up a meeting. I got his phone number and called him. He came to the studio that night. We sat for two hours. He played me a million songs. None of them were right for Janet, but he gets it. He just knows. My whole thing is that I knew he had songs for other people. He was getting ready to work with Dre, which was really cool. I told him it had to be tailored for Janet. I remember the next time we met, I introduced him to Janet and we sat there and he came up with “2 B Loved.” I called Tommy and asked him what kind of melody he would put over the song. At that point, the collaboration was on. They were like family and a big part of the creative process. We’re not averse to outside influence but it has to the right environment and be curated in the right way. Whether you like it or not, it sounds like Janet. To me that’s the biggest accomplishment. It’s a record that sounds like her. I hear people compare it to The Velvet Rope but it compares to the first five records.

Do you ever tour with her?

No. I’ve gone out to tweak a few things. She has a killer band and amazing singers and dancers. When she opened in Vancouver, I went there for a few days to work through a few things. Because I played everything I can walk up to the keyboard player and go, “This is the lick.” It’s actually kind of fun. I think it’s the best ensemble creatively that she’s ever had. They’re amazing